.........................................................

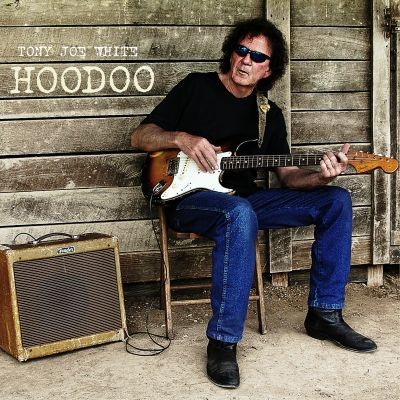

Tony Joe White’s music is as primal as a lizard’s backbone. It echoes from the magnolia groves and bayous of his Louisiana childhood, and looms into the present every time he unleashes the molasses and tanned-leather combination of his guitar and voice. The legendary songwriter’s new blues-based album, Bad Mouthin’, which arrives September 28, comes straight from the swamps with its blend of classics and five White originals, including two of the first songs he wrote—just before penning his breakthrough hits “Polk Salad Annie” and “A Rainy Night in Georgia” in 1967.

“When and where I grew up, blues was just about the only music I heard and truly loved,” says White, who’s 75 and, if anything, an even more visceral performer than in his youth. “I’ve always thought of myself as a blues musician, bottom line, because the blues is real, and I like to keep everything I do as real as it gets. So, I thought it was time to make a blues record that sounds the way I always loved the music.”

And that’s down-to-the-bone raw. Over the course of Bad Mouthin’ s 12 songs, White conjures a world of meaning that transcends the lyrics of classics like Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man,” Lightnin’ Hopkins’ “Awful Dreams,” and Charley Patton’s “Down the Dirt Road Blues,” using his deep river of a voice and the dark, spartan tones of his guitar to evoke the mystical South—a place where ghosts roam among abandoned pecan groves covered in Spanish moss and, indeed, the Devil might be encountered at a moonlit crossroads.

That White—who has penned hits and cuts for a compendium of fellow legends from Elvis Presley (“Poke Salad Annie”) to Brook Benton (“A Rainy Night in Georgia”) to Dusty Springfield (“Willie and Laura Mae Jones”) to Eric Clapton (“Did Somebody Make a Fool Out of You”) to Tina Tuner (“Steamy Windows”) to Willie Nelson (“Problem Child”) to Kenny Chesney (also “Steamy Windows”) to Robert Cray (who recorded White’s “Don’t Steal My Love” and “Aspen, Colorado” just last year)—would now craft a blues album after more than 50 years establishing himself as a heroic figure spanning the rock, country, R&B, and Americana genres is an incredible testament to his versatility as well as to his roots.

Mostly, Bad Mouthin’ features White accompanied solely by his road-worn 1965 Fender Stratocaster, the guitar he’s favored for his entire career. That’s all he needs to conjure the same kind of simmering emotional magic that John Lee Hooker distilled into his historic solo recordings—just one man and one guitar essentially defining what it means to be human in a story as simple and yet as profound as a Zen koan.

Five of Bad Mouthin’s stories, “Stockholm Blues,” “Rich Woman Blues,” “Cool Town Woman,” “Sundown Blues” and the title track, are plucked from his own past. When he sings “Bad Mouthin’,” about an abusive lover, White’s voice rings with the weariness of a man pushed to his limits. And in “Sundown Blues,” his spare lyrics capture the essence of a lonely heart over a slow smoky shuffle reminiscent of Hooker’s famed lowdown boogie beat.

On both of those tunes—which are early, rediscovered compositions that White first recorded for a local label in Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1966—and two others, drummer Bryan Owings backs White. Owings is White’s frequent accompanist on tour, in the two-man band format that White enjoys. Owings has also performed and recorded with Emmylou Harris, Justin Townes Earle, Wanda Jackson, and many others. The duo are joined by bassist Steve Forrest on two numbers. And the album was produced by Jody White and engineered by Ryan McFadden.

Their recording strategy was unconventional. White moved a hodgepodge of gear from his home to his barn, where two former horse stalls became their studio. “The cement-floor saddle room with unfinished wood paneling had a window unit air conditioning box that had to be turned off for recording,” says McFadden. “The next stall over had a dirt floor covered with glued composite board. Tony cancelled the first session, saying he couldn’t sing in there because of the chemical smell of the glue. When I went back, Tony had filled the stalls with bowls of coffee grounds, cups of rice, dryer sheets, and decorative brooms made of bound twigs that were drenched in a cinnamon scent, sold at grocery stores around Halloween.” After that, each song was cut live in one or two takes. The approach perfectly captured the laidback open sound and sliding chords with thumb-plucked low-string lines that defines White’s blues-drenched guitar style. Since White plays good and loud, they put his 1951 Fender Deluxe amplifier in the back of his Land Rover, so its bawling tones wouldn’t interfere with the vocals and percussion tracks.

White, who was born in 1943 as the youngest of seven children on a cotton farm about 20 miles from the nearest town, Oak Grove, Louisiana, says the foundation of his music “comes from hearing blues singers play guitar with maybe just a harmonica or stomping their feet for accompaniment.” Adding a drummer, he cut his teeth playing school dances and then moved on to nightclubs along the Texas and Louisiana “crawfish circuit” of rough and tumble watering holes. And then the hits started happening, with “Polk Salad Annie” reaching number eight on the pop charts in 1968. Two years later, Brook Benton’s recording of “A Rainy Night in Georgia” topped the soul charts, and it’s been a wild ride since: decades of touring and recording marked by hit songs and collaborations with the likes of Eric Clapton, Jerry Lee Lewis and Mark Knopfler.

“If there’s anything like a line connecting everything that I’ve done, I would say it’s realness,” says White. “Even my songs that are sweet little love ballads—those are all real, inspired by real love and real life. Being real, being focused on what’s really going on around you, is something I learned early in my life.”

He pauses and laughs. “When you’re a little kid growing up down in the swamps, and you step on a cottonmouth … that’s real.”

On Tour:

Media:

Links:

WEBSITE FACEBOOK TWITTERYep Roc Discography: